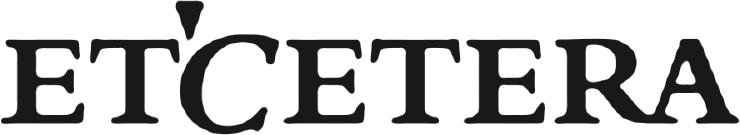

1. Fantaisie Pastorale Hongroise

Composer: Franz Doppler

Artist(s): Peter Verhoyen, Stefan De Schepper

2. Zigeunerweisen (1878)

Composer: Pablo de Sarasate

Artist(s): Peter Verhoyen, Stefan De Schepper

3. Tzigane (1924)

Composer: Maurice Ravel

Artist(s): Peter Verhoyen, Stefan De Schepper

4. Csárdás (1904)

Composer: Vittorio Monti

Artist(s): Peter Verhoyen, Stefan De Schepper

5. Hungarian Dance Nr. 5 (1879)

Composer: Johannes Brahms

Artist(s): Peter Verhoyen, Stefan De Schepper, Thomas Fabry

6. Hungarian Dance Nr. 6 (1879)

Composer: Anke Lauwers/Johannes Brahms

Artist(s): Peter Verhoyen, Stefan De Schepper

7. Duos (1931) – Ugyan Édes Komámasszony (Teasing Song)

Composer: Béla Bartók

Artist(s): Peter Verhoyen, Ilonka Kolthof

8. Duos (1931) – Burleszk (Burlesque)

Composer: Béla Bartók

Artist(s): Peter Verhoyen, Ilonka Kolthof

9. Duos (1931) – Magyar Nóta (Hungarian Song)

Composer: Béla Bartók

Artist(s): Peter Verhoyen, Ilonka Kolthof

10. Duos (1931) – Szól a Duda (Bagpipes)

Composer: Béla Bartók

Artist(s): Peter Verhoyen, Ilonka Kolthof

11. Duos (1931) – Arab Dal (Arabischer Gesang)

Composer: Béla Bartók

Artist(s): Peter Verhoyen, Ilonka Kolthof

12. Balada (1950)

Composer: György Ligeti

Artist(s): Peter Verhoyen, Ilonka Kolthof

13. Romanian Dances – Jocul Cu Bâta (Stick Dance)

Composer: Béla Bartók

Artist(s): Peter Verhoyen, Ann-Sofie Verhoyen

14. Romanian Dances – Brâul (Sash Dance)

Composer: Béla Bartók

Artist(s): Peter Verhoyen, Ann-Sofie Verhoyen

15. Romanian Dances – Pe Loc (In One Spot)

Composer: Béla Bartók

Artist(s): Peter Verhoyen, Ann-Sofie Verhoyen

16. Romanian Dances – Buciumeana (Dance from Bucsum)

Composer: Béla Bartók

Artist(s): Peter Verhoyen, Ann-Sofie Verhoyen

17. Romanian Dances – Poarga Româneasca (Romanian Polka)

Composer: Béla Bartók

Artist(s): Peter Verhoyen, Ann-Sofie Verhoyen

18. Romanian Dances – Ma Runt El (Fast Dance)

Composer: Béla Bartók

Artist(s): Peter Verhoyen, Ann-Sofie Verhoyen

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.